TŪĀRERE 1: TAU 0* - 3

*NOTE: 0 in Tau 0 - 3 accounts for those ākonga whose first day of kura occurs in the second half of the year. Effectively these ākonga will have only completed 6 months or less at kura. They would then be classified as year 1 the following year. This may differ from the practices of your kura.

Te Reo Matatini

Ngā tini mata o te reo - the many faces and facets of language

The term te reo matatini is credited to Professor Wharehuia Milroy, Dr Huirangi Waikerepuru, and Pēti Nohotima who sought to capture the essence of what would be required to deliver a programme of learning that upheld the heart of ‘te reo Māori’ in ways that acknowledge the deep and diverse forms that it takes and the wide range of functions it performs.

Te Reo Matatini therefore, is a culturally located term and is so much more than what is suggested in our print saturated world. As articulated by the late Hirini Melbourne:

“...The ancient world of the Māori was surrounded by writing in their daily life: the carvings on posts and houses, the marks on cloaks, the very architecture of the great meeting houses…”

“...The fact that texts - compositions, speeches, ritual replies, and so forth - were memorised, not written down, does not mean that the ancient Māori inhabited a world from which writing [as we know it], was absent. It was a world in which a variety of forms, written and oral gave vivid and complex expression to a culture..”

Melbourne's view presents an authentic pathway by which ākonga can gain access to, and create mātauranga, where they learn to articulate their understanding of the past, interact with their present and influence their future world because there are multiple contributors and multiple ways to get there.

Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā

Rangaranga = structure

ā-tā = the term in Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (2008) referencing pānui and tuhituhi

Rangaranga Reo ā-Ta is the term in te reo Māori for specific elements related to learning to read and write in te reo Māori.

The construction of a tukutuku panel, known as tuitui is used as a metaphor for Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā. Construction and design happens in a systematic and deliberate way. More often than not, the weavers already have a vision of the finished product and work together to realise that vision. A fully completed panel is called a tūrapa.

Construction typically involves two people. In the classroom setting, this represents the reciprocity of the teaching and learning process (i.e. ako) between the ākonga and the kaiako.

You start by building a frame on legs (te aroā weteoro me te aroā oromotu | phonological and phonemic awareness). The frame forms the foundation upon which the vertical slats (te oro arapū ā-tā | alphabetic principle) and the horizontal slats (ngā kūoro me te tautohu kupu | syllables and word recognition) are placed. The vertical slats are known as tautari while the horizontal slats are known as kaho.

A left overlapping wrapped stitch (Te Mātai Wetekupu | Morphology) and a right overlapping wrapped stitch (Te Tātaikupu | Syntax) bind the frame and the slats together giving the overall structure its stability. The stitch is known as tūmatakāhuki.

It is only then that you can start creating your pattern which embodies the meaning, the story you want to imbue into your panel (Te Kawenga Tikanga Reo | Semantics).

The materials used for building the frame and tukutuku panels themselves, were typically chosen based on what was readily available in the immediate environment of the weaver. Traditional materials such as toetoe, pīngao, and kiekie were commonly used. Now, with the introduction of modern and synthetic materials, weavers have greater choice and flexibility in both the construction of the frame and creation of the tukutuku pattern itself.

The tukutuku panel which here symbolises Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā, typically adorns the walls of the wharenui. The wharenui, if we are to continue the metaphor, represents te reo matatini - as signaled in Hirini Melbourne’s description.

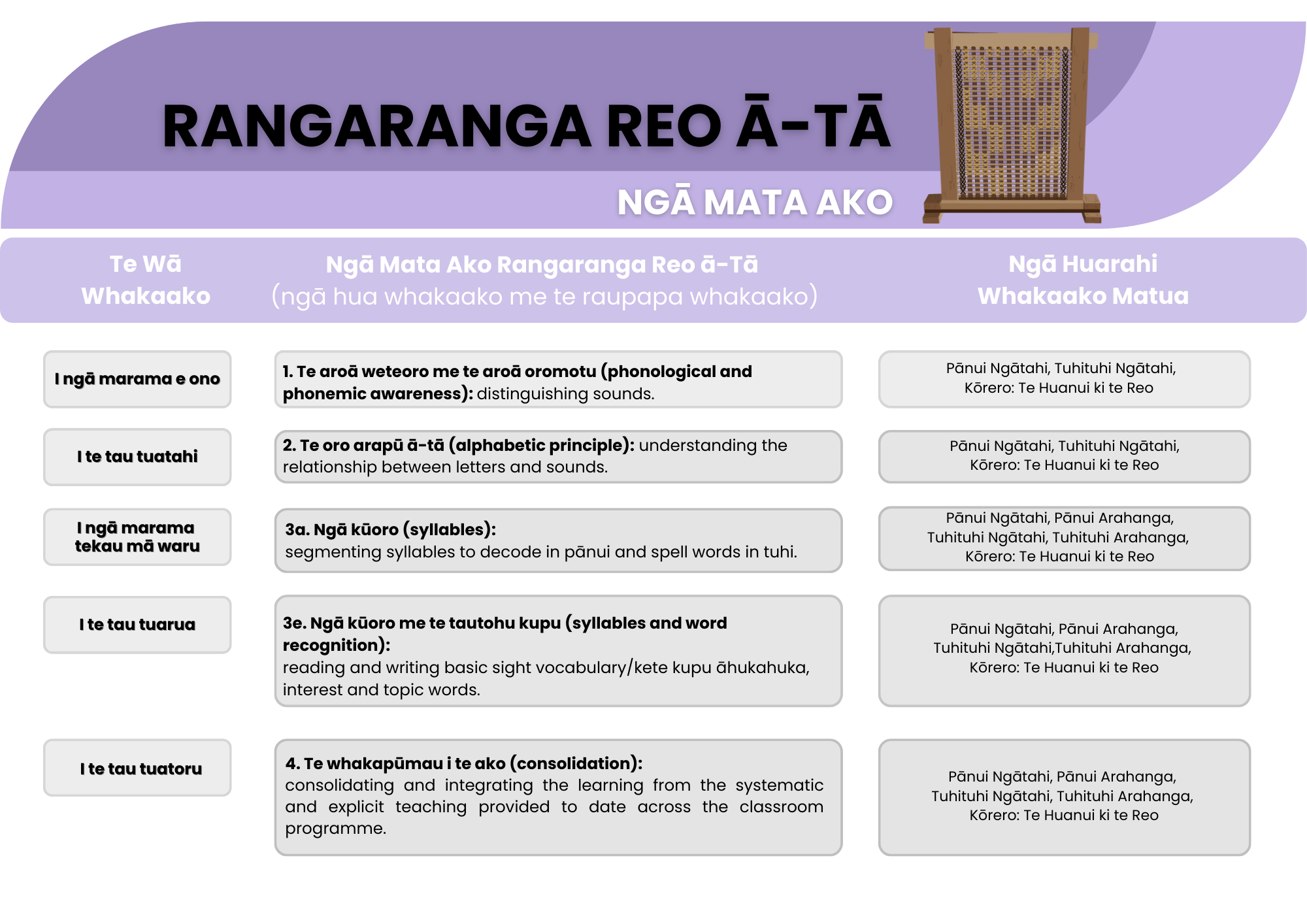

The following table shows the sequence of ngā mata ako Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā and ngā huarahi whakaako matua for kaiako working with ākonga tau 0-3.

While Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā involves the explicit, systematic, and cumulative teaching of pānui and tuhituhi, the reo matatini within which Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā sits must also explicitly attend to the development of oral language proficiency because the relationship between pānui, tuhituhi and kōrero is one of interdependence.

Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā considers:

Ngā hua whakaako (scope) - what needs to be taught.

Te raupapa whakaako (sequence) - the order in which the elements of Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā need to be taught.

Te wā whakaako (pace) - appropriate timing for teaching the elements of Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā, guided by broader evidence from ākonga learning and engagement that indicates readiness to effectively engage with these elements.

Ngā mata ako Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā:

Te aroā weteoro me te aroā oromotu phonological and phonemic awareness

Te oro arapū ā-tā alphabetic principle

Ngā kūoro me Te tautohu kupu syllables and word recognition

Te mātai wetekupu morphology

Te tātaikupu syntax

Te kawenga tikanga reo semantics

Te Whakarite Hōtaka

Te Reo Matatini Tau 1-4 A Literacy Handbook for Māori Medium Teachers

He kupu whakataki / Introduction 4

Whakarite ana i te wāhi ako / Creating a learning environment 8

He taonga te tamaiti / Start with the child 22

Te whakarite hōtaka / Planning your programme 28

Whakaako ana i te reo matatini / Teaching literacy 46

Te arotake me te whakaaroaro / Reviewing and reflecting 76

Kia whai wāhi mai te whānau / Including whānau 80

Tautoko mai / Getting support 84

The Science of Learning

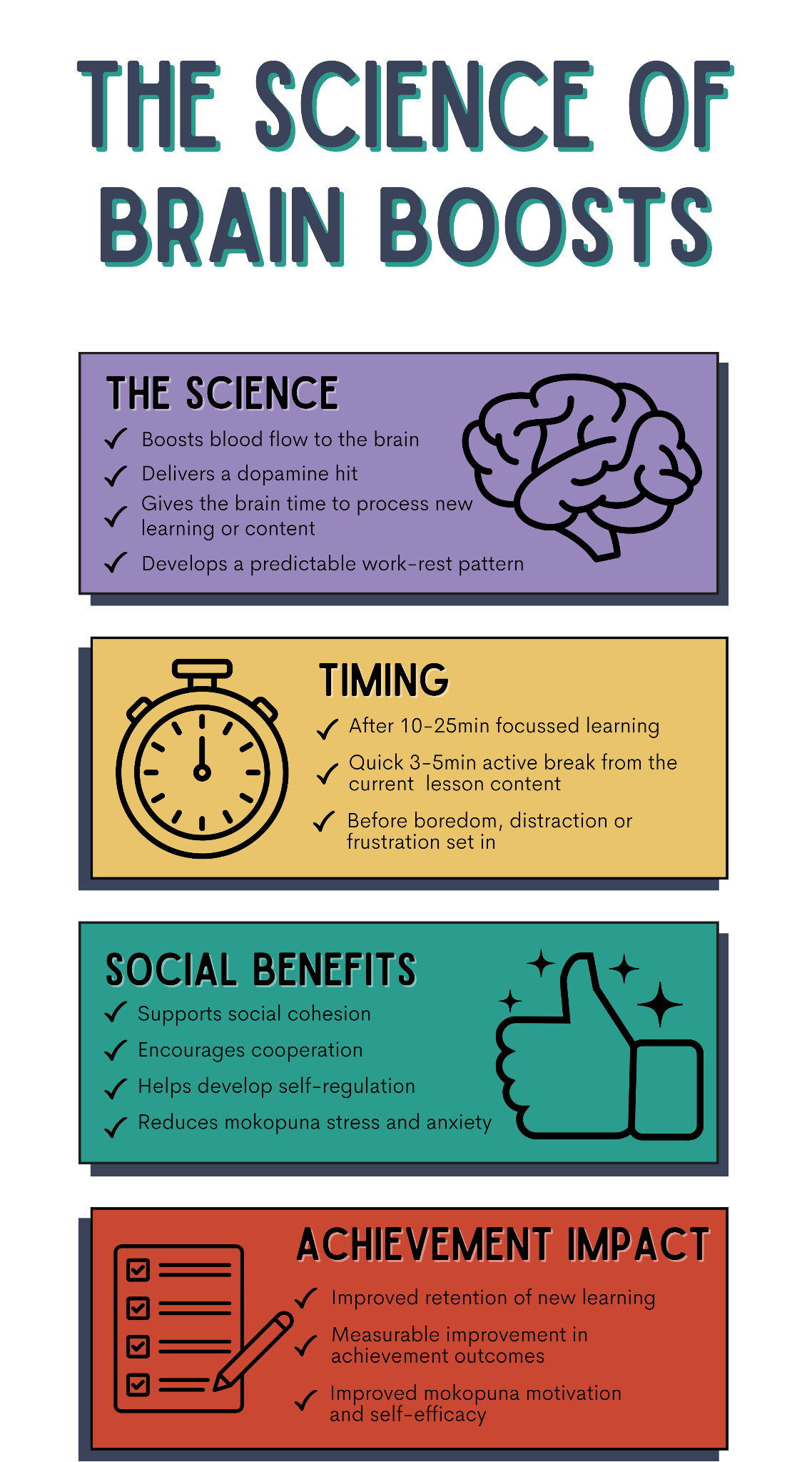

Guidance for Rangaranga Reo ā-Tā draws from cognitive neuroscience (specifically how the brain processes language for kōrero, pānui and tuhituhi), language acquisition theory and practice, research carried out in Māori-medium classrooms and the experience of Māori-medium educators dedicated to developing the personal, academic, linguistic and cultural identity of the ākonga.

Information processing

Information processing theory (video)

Information processing theory explained (video)

Working memory

Working memory (article and videos)

Cognitive load theory

Cognitive Load Theory: CLT (article and video)

CLT in the classroom (article)

Spaced repetition and retrieval practise

Reading is not hard-wired in the brain, and the neural pathways involved must be developed through successful instructional experiences.

Transcript:

What do we know about the complex process of learning to read? Surprisingly, a lot.

Scientific research collected over the past four decades reveals what happens in the brain, and what must happen in the classroom to enable skilful reading.

Most children learn to walk and talk naturally without a lot of support from adults, but reading is different.

Reading is not hardwired in the brain, and the neural pathways involved must be developed through successful instructional experiences.

Let’s look at the Reading Brain.

The parts of the brain that allow us to process sounds and recognise visual images are already in place at birth in the left hemisphere.

However, the phonological assembly region is not intact at birth.

This is the part of the brain that allows us to connect speech sounds with visual images, such as letters and enables reading.

And it must be built through explicit, systematic phonics instruction and practice with decoding.

The Science of Language Acquisition

It’s obvious that knowing more than one language can make certain things easier — like traveling or watching movies without subtitles. But are there other advantages to having a bilingual (or multilingual) brain?

Mia Nacamulli details the three types of bilingual brains and shows how knowing more than one language keeps your brain healthy, complex and actively engaged.

Transcript:

Habblas Español? Parlez-vous fançais? (Japanese)

If you answered “si” “oui” or (Japanese) and you are watching in English, chances are you belong to the world’s bilingual and multilingual majority.

And besides having an easier time travelling or watching movies without subtitles, knowing two or more languages means that your brain may actually look and work differently than those of your monolingual friends. So what does it really mean to know a language?

Language ability is typically measured in two active parts, speaking and writing, and two passive parts, listening and reading.

While a balanced bilingual has near equal abilities across the board in two languages, most bilinguals around the world know and use their languages in varying proportions. And depending on their situation and how they acquired each language they can be classified into three general types

For example, let’s take Gabriella, whose family immigrated to the US from Peru when she’s two years old. As a compound bilingual, Gabriella develops two linguistic codes simultaneously, with a single set of concepts learning both English and Spanish as she begins to process the world around her.

Her teenage brother, on the other hand, might be a coordinated bilingual, working with two sets of concepts, learning English in school, while continuing to speak Spanish at home and with friends.

Finally, Gabriella’s parents are likely to be subordinate bilinguals, who learn a secondary language by filtering it through their primary language.

Because all types of bilingual people can become fully proficient in a language regardless of accent or pronunciation, the difference may not be apparent to a casual observer. But recent advances in brain imaging technology have given neurolinguistics a glimpse how specific aspects of language learning affect the bilingual brain.

It’s well known that the brain’s left hemisphere is more dominant and analytical in logical processes, while the right hemisphere is more active in emotional and social ones, though this is a matter of degree, not an absolute split.

The fact that language involves both types of functions, while lateralisation develops gradually with age, has led to the critical period of hypothesis.

According to this theory, children learn languages more easily because the plasticity of their developing brains lets them use both hemispheres in language acquisition, while in most adults language is lateralised to one hemisphere, usually the left.

If this is true, learning a language in childhood may give you a more holistic grasp of its social and emotional context. Conversely, recent research showed, that people who learned a second language in adulthood, exhibit less emotional bias and a more irrational approach when confronting problems in the second language than in their native one.

But regardless of when you acquire additional languages, being multilingual gives your brain some remarkable advantages. Some of these are even visible, such as higher density of the grey matter, that contains most of your brains neurons and synapses, and more activity in certain regions when engaging a second language.

The heightened workout a bilingual brain receives throughout its life can also help delay the onset of diseases, like Alzheimer’s and dementia by as much as five years.

The ideas of major cognitive benefits to bilingualism may seem intuitive now, but it would have surprised earlier experts. Before the 1960’s, bilingualism was considered a handicap that slowed a child’s development by forcing them to spend too much energy distinguishing between languages, a view based largely on flawed studies.

And while a more recent study did show that reaction times and errors increase for some bilingual students in cross-language tests, it also showed that the effort and attention needed to switch between languages triggered more activity in and potentially strengthened the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

This is the part of the brain that plays a large role in executive function, problem-solving, switching between tasks, and focusing while filtering out irrelevant information.

So while bilingualism may not necessarily make you smarter, it does make your brain more healthy, complex and actively engaged, and even if you don’t have the good fortune of learning a second language as a child, it’s never too late to do yourself a favour and make the linguistic leap from “Hello” to “Hola” “Bonjur” or Nihao, because when it comes to our brains a little exercise can go a long way.

Additional Resources

Effective pedagogy

Te Toi Huarewa (report)

Te Kura Huanui _ Ko ngā kura o ngā ara angitū (report)

Te Kura Huanui - The Treasures of successful Pathways (English) (report)

Te Puāwaitanga Harakeke (Aromatawai) (position paper)

Glossaries

Paekupu (online dictionary)

He Kupu Taka - Te Marautanga o Aotearoa

Teaching pānui and tuhituhi

He ara whakaako i te pānui me te tuhituhi tau 1-3 (online manual)

Guide to teaching pānui and tuhituhi years 1-3 (online manual)

He Ara Ako i te Reo Matatini: Literacy Learning Progressions (online manual)

Te Tuhinga Hukihuki mō te Wāhanga Ako: Te Reo Rangatira (online manual)